Have you ever thought about the reasons for violence? Is it part of human nature, or are external factors such as society, family, or friends involved?

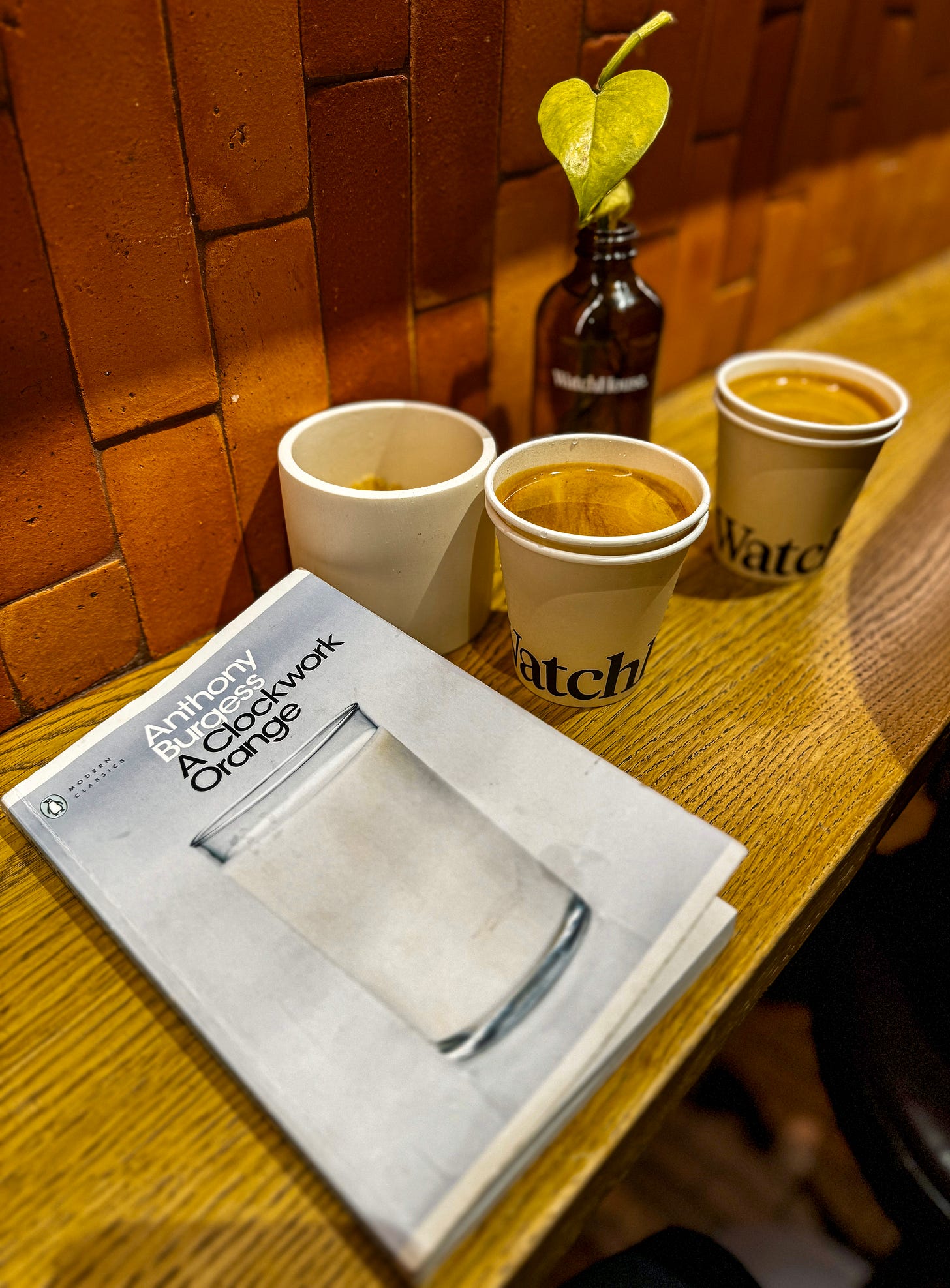

"A Clockwork Orange" tells the story of Alex, a charismatic teenager who leads a gang of "droogs" (in their teenage language: NADSAT) in a dystopian future. The book consists of 21 chapters, divided into three sections, with seven chapters in each section. Twenty-one is the age at which children traditionally become adults, and the same holds for Alex. The use of seven chapters is an implicit allusion to Shakespeare’s seven ages of man.

The narrator of the story is Alex, hailing from a dysfunctional working-class family. While Alex adores classical music and cares about his appearance, he also exhibits a deep-seated attraction to violence. This duality challenges the simplistic notion of individuals being solely good or evil, prompting the question:

Is violence inherent in human nature, or is it shaped by external factors?

One of their victims is a family with a sign reading HOME on their cottage. It's interesting how this name catches their eyes, leading them to commit violence. In the final chapters, when Alex is looking for a safe place to rest, he chooses this location again. It's as if he's trying to rebel against his family, and when vulnerable, he seeks a real home he never had, despite seemingly coming from a good family.

Throughout the story, Alex experiences betrayal by friends, family, prison roommates, and those who seem to be trying to help him. Despite trusting people repeatedly and facing betrayal each time, none of these instances prevent his redemption.

The story is about violence and raises important questions:

Can people with good taste in art still be violent? What is the role of art in life? Is violence inherent, or can people choose between good and evil?

Is violence a choice, or is it more like a curable disease?

And finally, what is a human without the right to choose?

Anthony Burgess makes you think. And I believe a good book is one that makes you think. His main character, Alex, is human despite his brutal actions. He's not just good or evil but a complex mixture of both, reflecting our own humanity. I appreciate the author’s ability to create characters who are not one-dimensional villains but flawed individuals.

The story was further popularized by Stanley Kubrick's 1971 film adaptation. While Stanley Kubrick's film remains a cinematic masterpiece, it's essential to note that it omits the final chapter present in the original novel. The American publisher removed the final chapter of the book to appeal to American readers, and the movie is based on that edition. This chapter offers crucial closure to Alex's journey, suggesting potential for redemption and raising further questions about the nature of free will and societal intervention.

Read the book, watch the movie and enjoy a great masterpiece.📖

I haven’t read or seen any version of “Clockwork Orange” for decades so my memory impressions are quite impressionistic. The cinematic version seared in a number of images. The literacy version was striking for its use of language.

I think you are right to focus on the deep questions each raises about violence which remain troubling, amusing, and confounding. Yes, I did say “amusing” but maybe I should rather have said “generative of laughter” because laughter can be an involuntary somatic response to trauma just as tears can be to joy. The questions raised are questions about humanity, and my thoughts are still currently in shaky alignment with Rene Gerard’s who seemed to see the process of “hominization” as a process involving reflective (mimetic) consciousness which included scapegoating, fear of scapegoating, and the fear and guilt arising from the apparent necessity of life to live off life (including other human life) in ways that are often predatory, exploitative, violent, and dangerous.

But I also feel like Violence is only one spur of a “trinity” of necessarily “sacred**” elements that also include Sexuality and Nurturance. Violence, Sexuality and Nurturance each have their allures and dangers. (The words “sacred” and “holy” refer to what must be set apart from ordinary life and consciousness to every extent possible so that humans can imagine ourselves to either be coherent “selves” or worthy parts of some coherent collectivity) Each of the three blends into the others, and each can tend to provoke fear, disgust, shame, and guilt though each can also be channeled and directed to promote feelings of exhilaration, ecstasy, and justification. I wouldn’t say that either Violence, Sexuality, or Nurturance were more important, central, or fundamental to the human need to achieves some sense of stable meaning or value. Nor would I say that controlling or channeling the three was the MOST important part of maintaining our humanity. After all, maintaining our humanity is only partly about maintaining a sense of meaning with regard to our bodies, our physical environments, and our cultural environments each rife with treacheries and treasures. Maintaining our humanity (or willingness to survive) also involves coping with all kinds of other dilemmas and challenges including a need to “escape”, “recreate” and shelter from the storms of what are so often incomprehensible, unmanageable, awe inspiring, and devastatingly barren though we sometimes resort to imagination, playful (or manipulative) fabrication, and genuine cultural innovation to make the forces within us and without us appear (temporarily) more reliably congenial.

**************

** in more complex and extensive cultures, especially those that could not be defined by kinships and where cultural coordination involved more than simple yearly cycles, the “sacred” became more focused on symbols of shared and collective identity connected to objects and stories related to disembodied paternal/maternal guardians and protectors of social orders and collective identities that transcended those of clans and tribes.