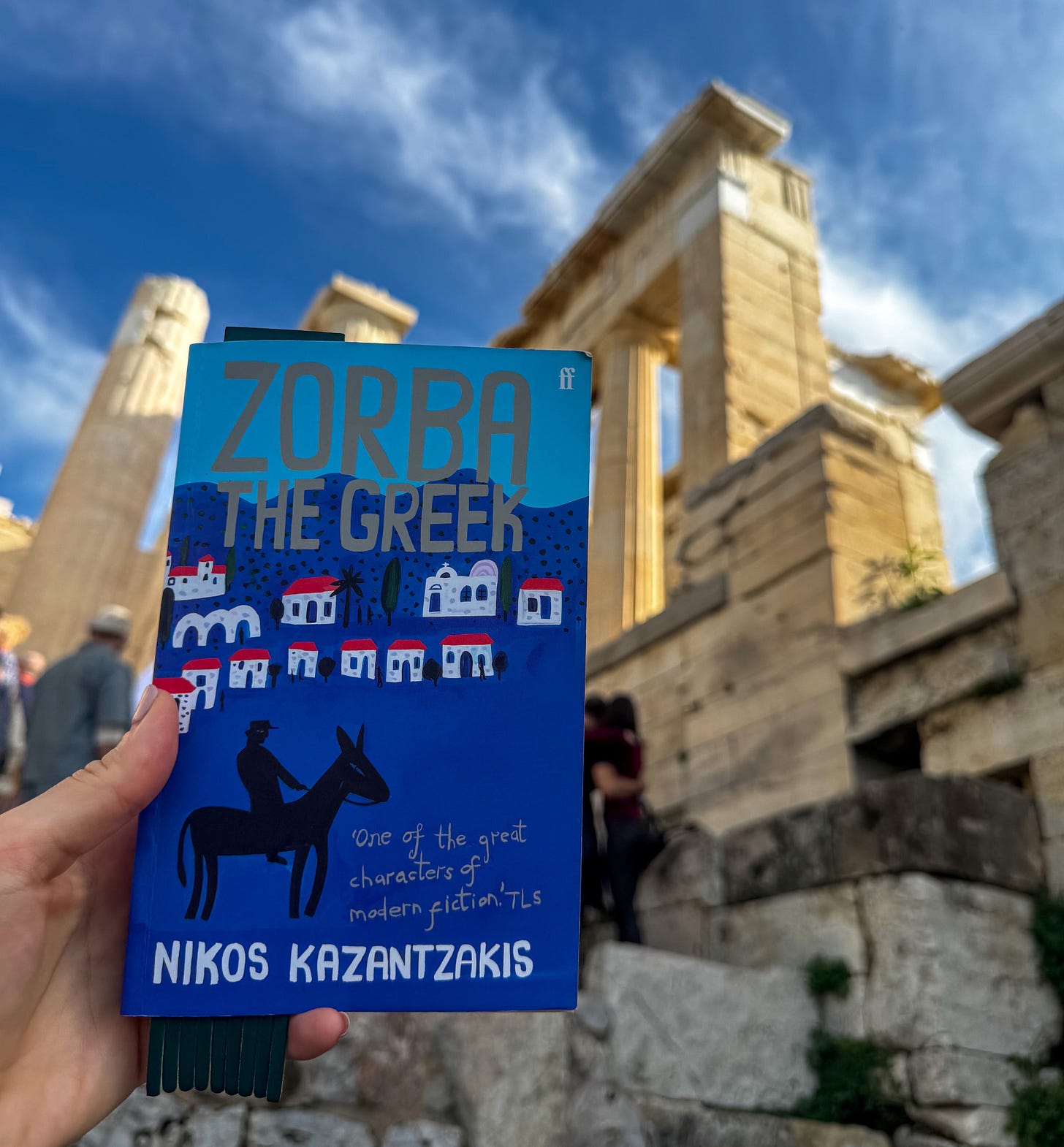

I first read Zorba the Greek six years ago, and I was completely mesmerised. It quickly became one of my favourite books, a place it held for years. I read it in Farsi, and for quite a long time it had been on my list to reread in English. When we decided to visit Athens, I told myself: this is the moment. So I read it again—this time discovering new layers, new meanings. And yes, I still liked it, but not in the same way as the first time. Is anything ever the same the second time we experience it?

Zorba the Greek is the story of two men. The narrator is a wealthy, bookish writer who decides to rent a lignite mine in Crete in an attempt to experience life beyond books for the first time. There, he meets Zorba—a wandering, free-spirited man who lives entirely in the present. The narrator hires him to cook and work in the mine, and what follows is not simply a partnership, but a profound encounter between two opposing ways of being.

The novel is deeply grounded in the belief that life has no inherent meaning beyond what we create ourselves. The narrator, fascinated by Buddhist philosophy and introspection, encounters Zorba, a man who lives on his own terms, guided not by theory but by instinct. Through Zorba, he discovers a radically different way of living—one centred on experience rather than thought, action rather than analysis.

For me, Zorba is unforgettable. An uneducated man who somehow knows how to live—to enjoy every minute of existence. He is existentialist in spirit but Dionysian in practice. He understands that life itself may be meaningless, and that meaning must be found in the smallest moments: eating, working, loving, dancing.

At its core, Zorba’s philosophy is simple: life must be lived with the whole body and soul, not observed from a distance. While the narrator searches for meaning through books, ideas, and restraint, Zorba finds it in action, sensation, love, pain, food, labour, music, and dance. For him, excessive thinking is a kind of fear.

I’ve stopped thinking about what happened yesterday.

I’ve stopped asking what will happen tomorrow.

What’s happening today—this very minute—that’s what matters.

“What are you doing at this moment, Zorba?”

“I’m sleeping.”

“Well, sleep well.”

“What are you doing at this moment, Zorba?”

“I’m working.”

“Well, work well.”

“What are you doing at this moment, Zorba?”

“I’m kissing a woman.”

“Well, kiss her well, Zorba! Forget everything else while you’re doing it; there’s nothing else on earth—only you and her!”

Zorba plays the santuri whenever he feels like it; his true language is dance. He spreads passion through everything he does, which is what makes him so vivid, so alive.

On our way back from the Acropolis, we saw a group of old men playing music, and one of them dancing freely in the street. I was certain—that was Zorba.

Reading it for the second time, this time, I noticed something new: the narrator himself. Perhaps I missed it before because of censorship in the Farsi edition, but the way he describes his distant friend, his emotional attachment to Zorba, and his lack of genuine interest in women made me wonder whether he might be grappling with his sexuality. Kazantzakis likely intended ambiguity. The narrator can be read as gay, bisexual, sexually repressed, or simply emotionally blocked. To me, he isn’t just a man who chooses books over life; he is a man who uses books as a shield against his own desires.

Last but not least, as much as I like this book, one troubling aspect is its mindset toward women. I understand that it was written in the 1940s, reflecting patriarchal Mediterranean societies where women were often reduced to bodies rather than minds—figures of desire or temptation rather than independent subjects. Still, understanding the context does not make it any easier to read the offensive conversations about women. The narrator, despite being an intellectual, never challenges this mindset. He plays with Madame Hortense’s feelings for his own amusement. When he witnesses violence against the widow he slept with the night before, he remains silent—more concerned about Zorba than her suffering, even justifying the violence in his thoughts, which is deeply troubling.

From Page to Screen: Zorba the Greek (1964 Film)

Another remarkable aspect of Zorba the Greek is its film adaptation. The 1964 film, starring Anthony Quinn, with music by Mikis Theodorakis, became a cornerstone of modern Greek cultural identity. The soundtrack is one of the most recognisable film scores in the world.

Mikis Theodorakis was one of my favourite musicians when I was younger. I remember filming a session for my guitar instructor and his band while they played his music. I was completely absorbed, dreaming of one day playing those melodies myself.

It’s astonishing how memories are tied to stories—those we read and those we live.

If you’re looking for a warm, unconventional, and deeply human book, put Zorba the Greek on your list. I’m sure you won’t regret it.

Before you go, read these two passages from the conversations between Zorba and the narrator, and tell me I’m not the only one who can’t stop thinking about them:

“Let people be, boss; don’t open their eyes. And supposing you did—what would they see? Their misery! Leave their eyes closed and let them dream.”

“Unless,” he said at last.

“Unless what?”

“Unless, when they open their eyes, you can show them a better world than the darkness they’re wandering in… Can you?”

And this:

“You understand—and that’s why you’ll never have any peace. If you didn’t understand, you’d be happy. What do you lack? You’re young, you have money, health—you lack nothing. Nothing, except one thing: folly.”

If you’ve already read this book—or plan to read it soon—I’d love to hear what you think.

Happy New Year’s Eve everyone! I hope you enjoyed my last post of the year! Thanks for reading☺️ If you liked this review, press ❤️ and share it with your friends!

I suspect I need to 'be more Zorba' in 2026. Great to read a review about a book that's never been on my radar. Thank you.

Happy New Year, Shideh, and thanks for sharing your talents in 2025!